Before I get too far removed from the classroom, I’m going to reflect on the fundamentals of information security that I learned in undergrad and applied in a system security course I took for fun as a master’s student. I’m somewhat writing this as a proactive measure against information loss–hopefully when I look back on this in a year or two I know considerably more about security than I do now. And if I don’t, then maybe this article will be a good starting point for future me to get back into it.

Dealing with People

Like most things in life, the hard part is dealing with people. A lot of people think the “system” in system security is referring to a computer system–as if that should be the focus of anyone seeking to keep something secure. In reality, the human component of that system is often the weak link. I think what system security really describes (and seeks to improve) is the process by which people interact with the machines they use and the data they store on them. Humans are brilliantly lazy. That’s why a lot of attempts to make computer systems more secure end as failures. I’ll give an example: for a long time, companies required employees to rotate passwords every so often. It’s a good idea in theory, as in the event that someone’s password is discovered, the intruder–who I’ll use proper syssec terminology and refer to as Trudy–will only have access until the password is rotated. But people are too lazy to think of an entirely new password every 60 days, and end up doing one of two things:

- Writing the password down on a piece of paper

- Appending a character to the old password to form a new one

Both make it much easier for Trudy to gain access, which is why NIST recommends against frequent password rotation. I think system security is slowly becoming more rooted in evidence-backed science than the rational principles it used to be based on, and that’s a good thing. Because humans do not behave rationally. We are predictably irrational, and security principles should take that into account.

Cryptographic Hash Functions

The basis of digital signatures and encryption, cryptographic hash functions take some input and produce an output string with a fixed length. The important properties of these functions is that they:

- are non-invertible, e.g. it is computationally challenging (nearly impossible) to figure out the input to the hash function given its output

- rarely produce collisions (according to pigeonhole principle there will be collisions, but finding them should be computationally hard)

Now even if you could have a perfect hash function that is truly non-invertible and never produces collisions (you can’t), there are still ways for attackers to circumvent it. But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Aside: Gold Standard & Dolev-Yao Model

I felt like these two unrelated topics were worth a mention, because they’re important but hard to tie in to just one part of this post. Instead, every security concept should be thought of in the context of these two topics. The Gold Standard consists of Authentication, Authorization, and Audit. I’m obviously paraphrasing, but basically what it says is that you maintain a secure system by forcing users to prove their identities, restricting the actions they can take based on their identity, and routinely monitoring your system for anything weird. A whole semester of system security in one run-on!

Dolev-Yao is a model of a network and attackers that specifies what types of attacks can be made, and it’s pretty generous to the attackers. In Dolev-Yao, attackers can intercept, modify, replay, and transmit communication on the public network infrastructure. Essentially the attackers are god, but god can’t break the laws of modular arithmetic. It’s a useful model because it allows you to prove that your system can resist Dolev-Yao attacks, which provides some guarantees about its security. But just because a system resists a Dolev-Yao attacker does not mean it is “secure”. Common attacks such as DoS are not included in this model, so you can’t just prove a system is Dolev-Yao-proof and call it a day.

Asymmetric vs Symmetric Key Cryptography

Ideally, all information passing across the internet would be encrypted with symmetric key cryptography, where both the sender and recipient use the same key known only to them to encrypt and decrypt the ciphertext. Symmetric key cryptography is much faster than asymmetric key cryptography, but suffers from a problem: how do two people physically separated across the internet choose a secret key? Assuming they can’t meet up in person to agree on a symmetric key to use, they’ll need asymmetric key cryptography. In asymmetric key cryptography, a user can publish a public key which can be used by anyone on the internet to encrypt a message (maybe a message containing a symmetric key to use!) and only the user with the private key can decrypt messages that have been encrypted with his public key. This is usually encrypted communications occur, where an asymmetric algorithm like RSA is used to share a key for a symmetric key algorithm such as AES256, which is much faster and handles the bulk of encryption and decryption.

Authentication

The challenge with authenticating over the internet is determining if someone is actually who he claims to be. Assume that you come across the website luke-griff.github.io where a public RSA key is posted, allowing you to use that key, encrypt your confidential message, and send your now encrypted message safely to luke griff. That method of communication securely transfers data over the dangerous public internet, but it doesn’t guarantee that who you sent it to is actually luke griff. It could be an impersonator hosting a mirror of that website, and now you’ve just sent them your secret data. So how do we establish identity?

The current method of authentication relies on a hierarchy of established Certificate Authorities (CA) which authenticate users based on trust. For example, my identity is known by my local ISP CA, which trusts a parent CA for the United States, which in turn trusts a CA in Singapore. The website I want to visit happens to be known to that CA in Singapore, which communicates through the chain of CAs and issues a certificate of validity for that website in Singapore, which tells me that the site is who it says it is. This hierarchy relies on a chain of trust, and obviously it unravels if any one of these CAs in the chain is malicious. By design this places a lot of power with CAs, which is fine if you have a lot of faith that CAs will act honorably, but that isn’t always the case.

Passwords

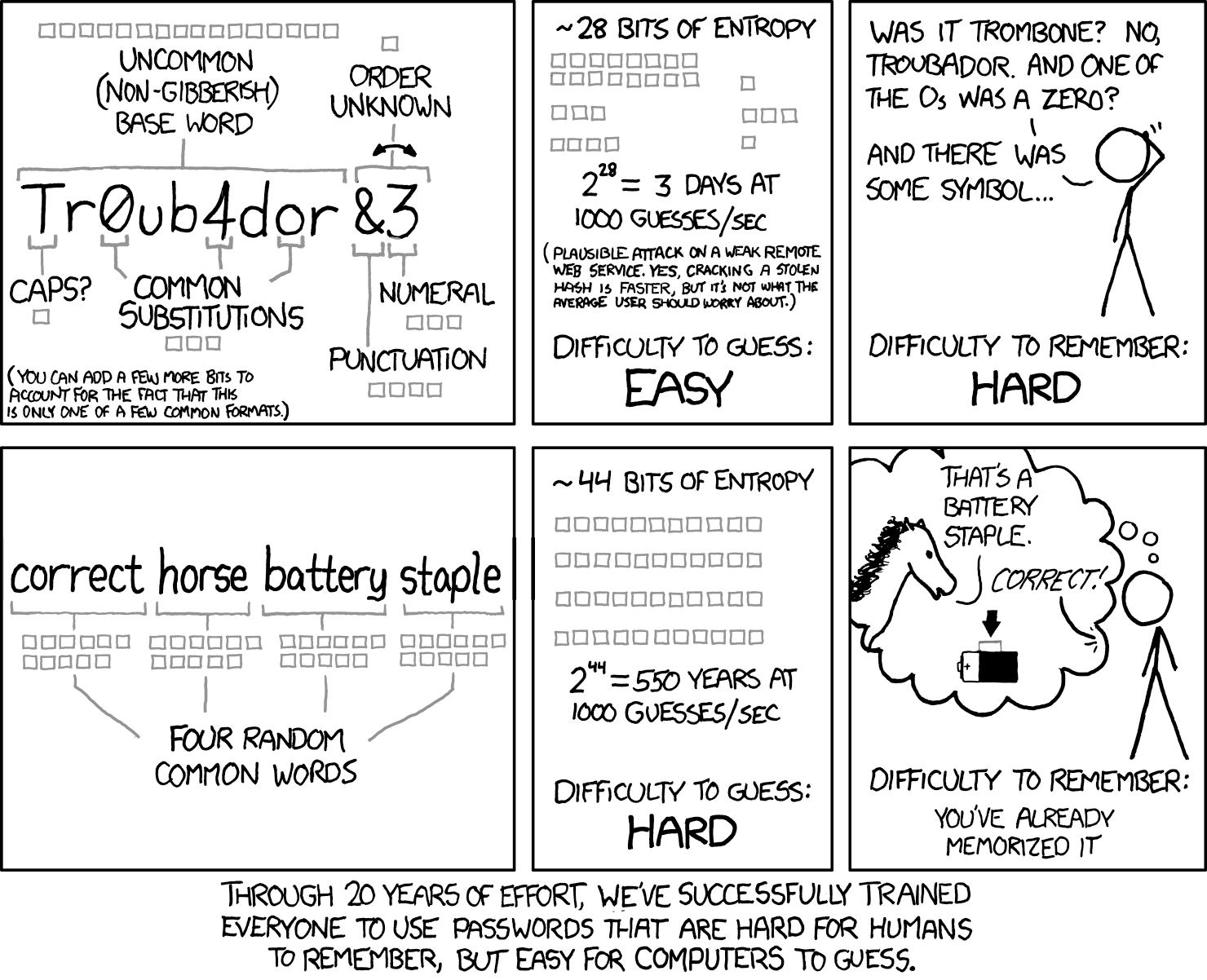

First, I need to acknowledge the xkcd comic in the header of this post. With password security, we want to ensure the entropy of our password is large. Entropy, in cryptographic contexts, is a measure of randomness. It’s a proxy for how difficult it would be to brute-force a password, and mathematically the number of bits of entropy of some password is given by \(\log_2{\text{(#password permutations)}}\). I like the xkcd comic because it raises a valid point, that sufficient entropy could be achieved by choosing four words uniformly at random from a large dictionary of english words. This brings us back to the “dealing with people” portion of this post. If four random words is easier to remember and computationally just as hard to crack as a complex string of ASCII characters, the approach that reduces the likelihood that lazy humans create vulnerabilities is the approach to use.

Today, every OS, web browser, and website has some form of secrets manager, which is essentially a database of username password pairs. Aside from social engineering, the obvious thing to attack is the secrets manager database itself. After several database leaks, the information security industry wised up and began storing hashed passwords in their databases. In the event of a database leak, attackers would only have access to hashed values. Since cryptographic hashes are non-invertible, the hashed value is worthless and unusable. Unfortunately there’s a lot of money to be made stealing people’s secrets, so attackers invented clever ways to get around this.

Salt & Pepper

Mr. Pepper & Mrs. Salt, from Blue's Clues

Attackers use a combination of brute-force and human laziness to circumvent hashed passwords. If attackers spend some time pre-computing a mapping from common passwords (e.g. “password”, “p@ssword”, “p@$$word”) to their associated hashed value, then they can determine the actual password of many passwords from their hash. These mappings are called rainbow tables, and rainbow tables exist that are billions of entries long. Here’s an example rainbow table with three entries:

- 5baa61e4c9b93f3f0682250b6cf8331b7ee68fd8 –> “password”

- 36e618512a68721f032470bb0891adef3362cfa9 –> “p@ssword”

- 59fb2e716bdeb67a0d761385331285de0b6a46ff –> “p@$$word”

By pre-computing the rainbow table which can be used indefinitely, attackers circumvent the non-invertible property of cryptographic hashes. To defend against this, we use salt.

Salt

Salt is a defense against rainbow tables. For each password created, a short random string (the salt) is generated and then concatenated to the password before hashing. Then the database stores the hashed value and the unencrypted salt with it. Now when a user goes to authenticate, the database will concatenate the stored salt with the input and see if the hash matches the stored value. Importantly, this means that the rainbow table is useless, because the salt has introduced random variations to the common passwords thus changing their hashed values. For example, early unix systems used 12 bits of salt, representing the system time when the password was created, to keep passwords secure.

Pepper

What if the attacker is particularly motivated to break one individual’s password and has the computational power to brute-force it in a reasonable time frame? Salt doesn’t defend against brute-forcing, since the salt is stored unencrypted and an attacker will be able to see it in the event of a leak. Pepper is the addition of a very short random string to the end of a password. When a user creates a password, the password concatenated with the pepper is hashed and that hash is stored in the database. When the user attempts to authenticate, the system will try out all possible combinations of pepper concatenated with their input to see if it matches the stored hash. As an example, let’s say the pepper is a single upper case alphabetic character. If I set my password as “ilovedogs”, a random pepper is chosen (let’s say ‘T’) and concatenated to my password before hashing. So the value that actually gets stored in the database is hash("ilovedogsT") and then the ‘T’ is thrown away. When I attempt to authenticate, the program will try all possible pepper values with the password I entered (“ilovedogsA”, “ilovedogsB”, ilovedogsC”, .. , “ilovedogsT”) until it finds one whose hash matches the stored value. This means that our brute-forcing attacker will need to wait 26x longer to brute-force my password. Obviously the length of the pepper is a trade-off. The longer it is, the harder it is to brute-force, but the more computation it takes for a valid user to authenticate. This trade-off is what needs to be determined based on your system and how motivated attackers may be to break into it.