The “conventional” approach to supervised machine learning usually follows this recipe:

- Some fixed dataset \(\mathcal{D}\) of labeled data \((x, y)\) is split into train, validation, and test sets

- Some ML model(s) are trained on the train set using an optimization method, different models and hyperparameters are evaluated using the validation set

- Once you’re satisfied, the trained model is evaluated using the test set. You report the test performance to your boss, and if it’s good she gives you a raise

- The model is compressed or distilled for faster inference and lower memory/power costs, if necessary

- Deployment

Unfortunately, there are lots of situations that complicate this. What if the objective you’re using ML to accomplish is evolving? For example, if your ML model is attempting to recommend someone a movie, how will it adapt to that individual’s changing movie preferences, which can’t be captured by a fixed dataset representing the individual’s past preferences? Or let’s raise another issue. What if our dataset is fragmented, and each portion of the data is controlled by a different group (individual/organization/country) who is unwilling to share data with the other groups, for security, privacy, or other reasons. How do you train a model if you aren’t permitted to access the data directly? I’ve described a solution to both of these problems and (just for fun) detailed how I believe Apple’s face ID works.

Online Learning

Unlike the conventional offline learning setting which has a designated training phase followed by inference, online learning interleaves the two. Usually this occurs when data comes in sequentially, we make a prediction given the data, we update our model’s parameters given some feedback about the prediction the model just made, and the cycle repeats. One way to do this is through online gradient descent, where our parameter update is given by \(w_{t + 1} = w_t - \alpha \nabla_{w_t}\ell(h_{w_t}(x_t), y_t)\). Hopefully this looks a lot like SGD, because it is very similar. For online learning with feedback (labels) our procedure is

- Receive new input \(x_t\), make a prediction \(y_t\) using \(w_t\)

- Update our parameters for the next time step using feedback \(\hat{y_t}\): \(w_{t + 1} = w_t - \alpha \nabla_{w_t}\ell(h_{w_t}(x_t), \hat{y_t})\)

This process continues as long as there’s data streaming in. For high-frequency trading models, data might be coming in every millisecond. For Netflix movie recommendations, data might come in once a week. And for Gmail’s spam filter model, data comes in once a year when I get frustrated enough to actually report something as spam.

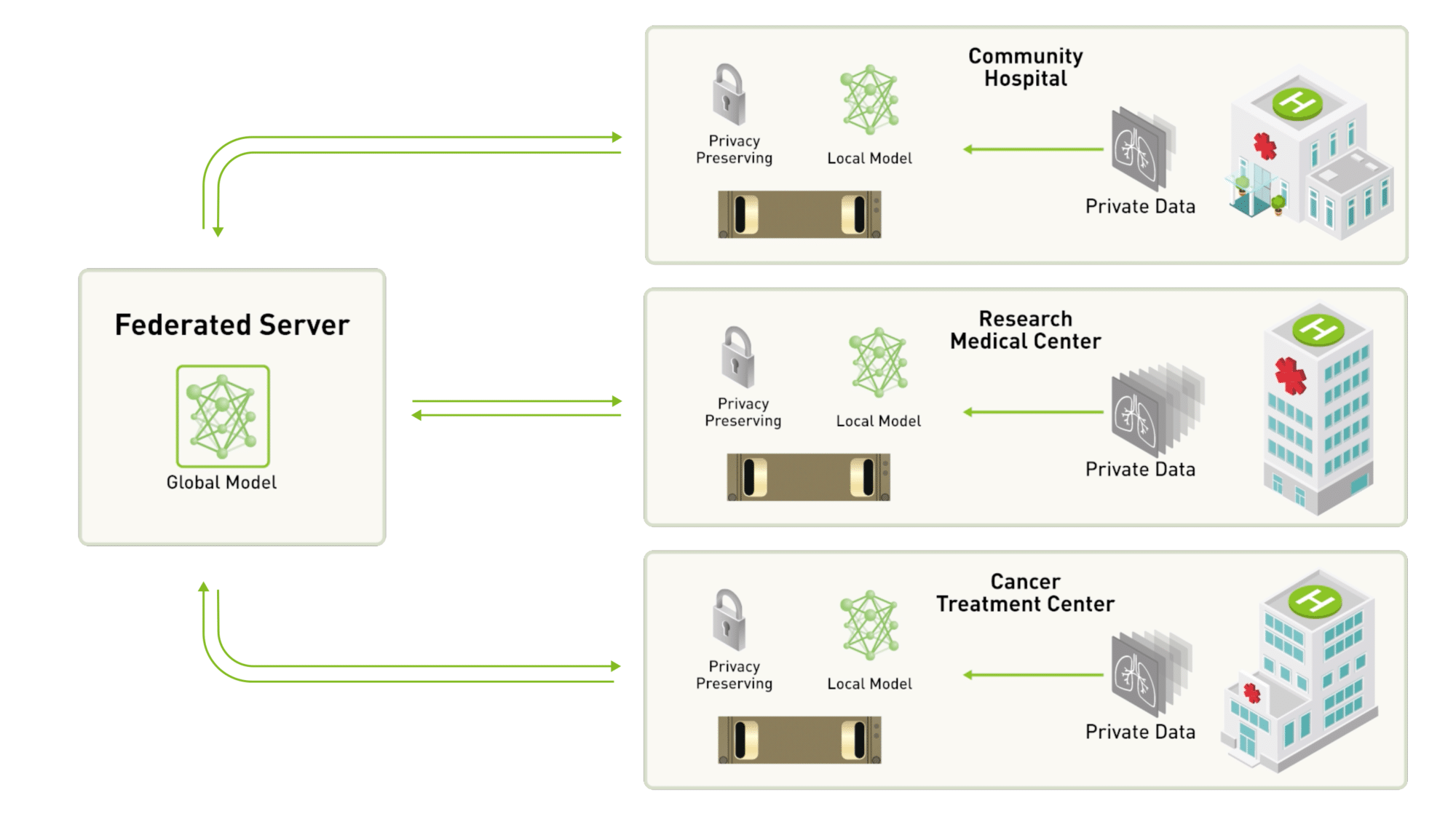

Federated Learning

How would you design a machine learning system to identify disease \(Z\) given some patient data? In the US, HIPAA prevents the distribution of patient data, potentially even among healthcare providers (without explicit consent). Health information is scattered across thousands of hospitals, which makes training models on a large dataset of patient information infeasible. Federated learning remedies this problem, though it was originally created as a way to train models using private text message data from phones without sending that data to the cloud.

Federated learning uses a client server model, where each client trains a copy of the global model on its own dataset. The parameter updates from each client are sent to the server, where they are averaged and used to update the global parameters. A copy of the updated global parameters are then distributed to each client, and the process iterates. In our hospital example, this means that each hospital uses its own set of patient information for the gradient computation, and sends its gradients (which notably doesn’t contain any patient information) to the server for averaging. The server then updates the global parameters and redistributes them to all hospitals. The beauty of federated learning is its simplicity. We really only have four hyperparameters:

- \(\alpha\), the learning rate

- \(C\), the fraction of clients that perform computation each update step (in most cases \(C=1\))

- \(E\), the number of iterations each client performs on its dataset

- \(B\), the batch size used by each client

If you’ve ever tried to do SGD at scale, you might be wondering how this is any different from a parameter server architecture. Indeed our methodology is very similar, but our assumptions about the data are not the same. Notably, in federated learning our data is not independent and identically distributed (IID) nor is it balanced. In our hospital example, this is because the patient demographics of a hospital in a Greenwich, CT isn’t necessarily representative of the population at large, and because large hospitals contribute more data than small ones. Nonetheless, federated learning has been shown to be very effective, and will likely become very popular as concerns over data privacy grow. [1]

Reverse Engineering Face ID

I like to think about the practical applications of machine learning–hence the patient data example for federated learning, and spam emails, recommendation systems, and high-frequency trading for online learning. But I wanted to go a little further and explain how I think Apple’s Face ID works (that information is proprietary, so this is mostly investigative/guesswork).

Face ID needs to be low inference, can’t consume a lot of memory, and can’t require too much compute. It also needs to be easy to enable, and must evolve with the person who is authenticating. This means it shouldn’t stop working as I grow out my hair and beard. Ideally, it should also still recognize me if I’m wearing glasses, a hat, or even a mask. Finally, we want to make a marketable guarantee about our system, such as Apple’s claim that Face ID has a false positive rate of \(1:1,000,000\).

First, Face ID isn’t training a network when you register your face–instead, it’s using a network that Apple trained using thousands (millions?) of faces. Your iPhone has a copy (probably a distilled copy—Apple loves model distillation) locally. This model is not a classifier. It was likely trained with a Siamese Neural Network architecture to take TrueDepth images and infrared images as input and produce an embedding \(\mathbb{R}^{128}\). That is, the model takes a scan of your face and converts it to a low-dimensional (\(128\) dimensions) latent space. During training, the model uses triplet loss to arrange faces in the latent space so that images of the same face should be very close together, while images of different faces shouldn’t be close. Once the model is trained and distilled, it gets evaluated for that nice false positive number. When you register your face, Face ID takes a few scans of your face and puts them through the network, producing a vector (embedding) of your face in the latent space. This embedding is stored in the “Secure Enclave” to be used for future authentication. When you attempt to authenticate, a scan is taken of your face and given as input to the model. It produces an embedding which is compared to the stored embedding using some distance metric like euclidean distance. The \(1:1,000,000\) false positive rate is set using this distance metric. Apple ran experiments to determine the maximum distance between stored and authentication embeddings that results in a false positive rate of \(1:1,000,000\). Note that because our network is pre-trained, the registration cost is nonexistent—all the model needs is one pass to store an original embedding that future authentication attempts can be compared to.

Great! Now we just need to make sure our model recognizes faces that change over time. Apple states,

“Face ID data … will be refined and updated as you use Face ID to improve your experience, including when you successfully authenticate. Face ID will also update this data when it detects a close match but a passcode is subsequently entered to unlock the device.” [2]

This indicates that, periodically, Face ID will change the stored embedding to stay up-to-date with the user’s changing face. One final question: how does Face ID recognize faces with and without glasses, hats, and masks? There are a couple options, and I’m honestly not sure what Apple does so I’ll present a few possibilities.

- The distance threshold is large enough that no special consideration is needed or features that indicate the presence/absence of glasses, hats, and masks were identified during training and are ignored when comparing embeddings.

- Several embeddings are stored for the face–one with glasses and one without, for example.

- Given vectors for glasses, hats, masks identified during training, vector arithmetic extends the single stored embedding to encode a face with glasses, hat, or mask. The authentication embedding is compared to the stored embedding with each of these transformations applied.

Of these, option \(3\) is the least likely, though it is certainly possible. It’s also possible that it’s none of the above. So that’s it. That’s how I think Face ID works. Note that the application evolves, but does not use online learning–the model’s weights aren’t updated once they’re put on the iPhone, just the stored embedding is updated.

References

[1] Communication-Efficient Learning of Deep Networks from Decentralized Data